Choosing an Indigenous Subject for a Statue

First published in the Busselton-Dunsborough Mail, June 21, 2017

We ‘wedulah’ (whitefellas) can do better than complain about the choice of Gaywal for the representative statue of a Noongar in Busselton. We might instead take a solemn moment to remember that after Gaywal speared George Layman, a posse of settlers, including humanitarian John Bussell, hunted down Noongars indiscriminately and according to the Perth Gazette of the time killed ‘at least seven Wardandi’.

The settlers were unwilling to share land. Under John Bussell’s leadership, they were generous to the local Aboriginal people in every other respect, except the land needed for their mission of settlement. John Bussell seems to have been genuinely baffled that the first people did not immediately see the benefits of colonialization and jump at them. The Wardandi, on the other hand, were equally baffled at newcomers who would take all the land and refuse to share the necessities it provided.

The tensions were inevitable. Vernon and Alfred Bussell grew vexed because the Noongars continued to trespass to hunt kangaroos. The hungry Noongars took cattle and speared horses. The Bussells started taking hostages, including women and ‘a little girl’. The dispute escalated until a Bussell servant was killed by the Noongars. According to E.O.G. Shann’s 1926 Cattle Chosen, nine Wardandi men and women were shot dead in retaliation.

Isn’t it time we ‘wedulah’ accepted both that the Bussells and the Laymans deserve honour for their noble achievements in settling the Vasse and also that lethal misunderstandings arose between our forebears and the Noongar people? It’s a sobering history, but to ignore it is an ongoing disrespecting of the first people. Acknowledging this past seems to me essential if we are to arrive at reconciliation and healing.

Cattle Chosen

The Bussells & Molloys and the local Wardandi people

The Bussells, Molloys

and the difficult relationship with local Noongars

I salute John Bussell and Georgiana Molloy as the founders of our church. When they landed at Cape Leeuwin in 1830 and camped on the beach, Georgiana Molloy and John Bussell made a commitment to meet every Sunday afternoon for Evening Prayer. John Bussell and John and Georgiana Molloy, as far as we know, met every Sunday for worship while they were in Augusta, when they moved to the Vasse in 1834, and when Bussell married the widow Charlotte Cookworthy in 1838 and brought his bride back to Australia. Charlotte was excommunicated from the Plymouth Brethren when she married John, and her three children were kidnapped to join them on the Montreal back to Western Australia.

The worship continued when St Mary’s was built in 1845, and so until today. We celebrate 186 years of continuous Sunday worship. That’s quite an achievement in Australia, and a credit to the Bussells and the Molloys.

On October 4, we celebrate St Francis of Assisi. We remember St Francis, firstly for his love of Jesus, and then for his love of creation. For him, every creature carried its own story from God. Jesus was the Word of God, with a capital ‘W’. Every animal, every plant, was a little Word of God.

Georgiana Molloy committed to worship because of her strong personal faith. She had been influenced by the revival in Scotland and had arrived in Western Australia as an enthusiastic Christian.

Georgiana Molloy

Life turned out to be hard and it tested her faith.

She sent plant seeds and specimens from Busselton back to England to the botanist Captain James Mangles. Plants were her passion that comforted her in her difficult life. She had to put up with the arduous conditions of being a settler, her eldest daughter dying at birth, and her son drowned in a well at 19 months. Her husband John was resident magistrate and he often spent time away from home. Plants became a solace for her. She thanked God for them as part of creation. In her diaries she deepens and develops her theology of plants and creation.

John Bussell had a slightly different take on faith. He had trained for ordination in England but his father died before he could be ordained, and migration to the Swan River seemed an excellent idea for the family. Bussell saw establishing a farm in the colony as a missionary activity. In his mind, the aborigines were uncivilised and living in poverty because of that. His farm would grow food and provide employment for the aborigines. They could be labourers on his farm and he would turn them into English Christian men.

In 2016, we can be critical of this idea of mission, but in 1830 Bussell’s ideas were praiseworthy and mainstream.

It’s hard for us now to imagine how difficult it was to settle this colony. It may have been an adventure, but the Bussells and Molloys were often hungry, often on the edge of exhaustion, just on the edge of surviving, or not surviving.

So the local Wardandi people, the Noongars, became a complication for the incomers. The Noongars probably had a better idea of what the Bussells and the Molloys were experiencing than the Bussells and Molloys had of the aborigines.

Goomal – Western Ringtail Possum

The Noongars had a very different idea of animals. They lived in nature alongside yongar, the kangaroo, goomal, the possum and all the other native animals. The yongar, the goomal and yorrn, the bobtail, were there to feed them, so they hunted and killed and ate, but they respected the animals, and limited how many they could take. Where I grew up in Tambellup, the yorrn had a special value; it was a kind of tribal totem.

The animals and the people lived in the land, and the land was the natural system that held it all together and sustained the people. The land didn’t belong to people. We know now that Noongars believe people belong to the land.

In John Bussell’s mindset, the Governor of the colony had granted him Cattle Chosen, so he, John Bussell was the rightful owner of the land, responsible to develop it along with all the other colonisers, so that the whole Colony could grow and prosper.

But the Noongars’ different beliefs meant there were clashes. The fact that the Noongars roamed the land at will meant they didn’t respect the property of the Bussells. They would turn up at the house – not meaning any harm – but frightening anyone who came upon them suddenly. Because this happened, the Bussells and the Molloys were even more on edge. We could compare their emotional state to suddenly coming upon a dugite at our back step.

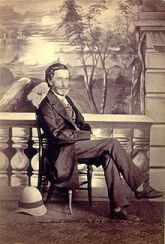

John Garrett Bussell

The white men needed the yongar to supplement their diet, and hunted them. The Noongars would take cattle, usually taking one cow for one kangaroo killed by the white fellas. The Bussells reacted, on two occasions at least, by shooting several Noongars. Something similar happened at Wonnerup as well after George Layman was speared. His grave, as well as the Bussells’ graves are outside St Mary’s. There are no Noongar graves.

The Noongars were dumbfounded at these reactions. It’s easy with hindsight to see what an over-reaction murdering seven people was, and then another seven, ‘with more women and children than the first time,’ as Mrs Bussell wrote home.

For me, it is important to remember these things about the people who founded our church. They were people of their time. They were frightened and on the edge, but their intentions were to build the community of Christ. They didn’t set out to be evil.

What we haven’t done, I don’t think, is to acknowledge the actions of our ancestors. Noongars today regard this history as unhealed, unreconciled. One aspect of mission I would like to see at St Mary’s is reaching out to local Noongars in a spirit of confession and conciliation.